Walking through the narrow lanes and bustling seaside of Fort Kochi in late July, I can’t help but wonder about the stories that reside in the town’s folds. I reach Pepper House on Kalvathi Road, the address of graphic artist Orijit Sen’s month-long non-fiction comics workshop organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation in the run-up to the Biennale scheduled to take place from December 2018 to March 2019. The participants, all 11 of them, are immersed in research notes, storyboard sketches and first drafts within the studio space on the upper floor. Their work, each unique in style and subject, draws from their engagement with the community, a key aspect of the workshop. (The workshop concluded just before the floods in Kerala turned disastrous in the beginning of August, but rain finds its way into many of their sketches, almost a harbinger of what is to come.) I chat with Sen later that evening. We talk about the workshop and the processes behind it, but also about the medium of comics itself, how it is an effective tool for social observation, and what sets Indian comics apart. Excerpts from our conversation:

Could you tell us a little bit about the workshop? How did the idea come about and what are its objectives?

Well, the reason it’s happening is because I was approached by the Kochi Biennale Foundation to do what we call a Master Practice Studio, where they invite an established practitioner of a particular medium to conduct a month-long workshop for a group of participants. The idea behind it is to have something which is a little bit more intensive than a workshop, more in the nature of an apprenticeship, but within the [time] limit of a month. Here, people are able to learn not just a set of skills but perhaps an approach to work. The process is already very rewarding. But I’m hoping that the outcomes too will be strong and we will be able to perhaps put them together as an anthology.

What does the process of creating non-fiction comics involve?

Non-fiction requires a research aspect. Not just recording or listening to people—that’s one part of it. The other is to draw those people, places and things. So the more primary research in my mind is visual research. This visual research brings in a lot of rigour and discipline to the craft. It’s a world by itself. It means being able to notice, and record through drawing, the reality that you are going to present: the people, the places they inhabit, their work.

What has been the focus of the research that the participants are engaged in and how has that progressed?

I wanted to focus our stories on the Kochi that the people here live and experience. And it’s very interesting how that process has happened, from stages of being this outsider, who is gazing at the life of people here, to beginning to see it from the inside. I mean, you can never look at things as an insider but you are in that space between.

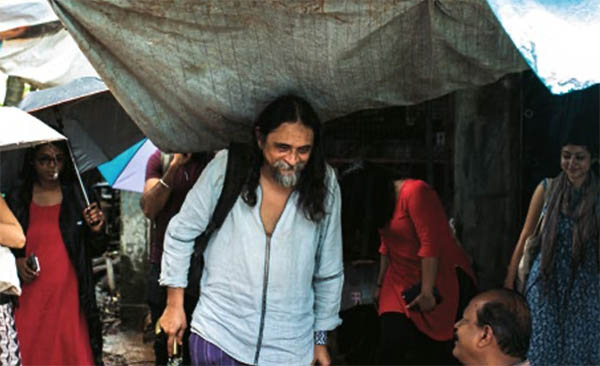

A simple example is that there’s a person who initially appeared to two of my participants to be a bit of a mystic, a kind of person who had a special quality to him. As they started going deeper into his story, they came to me and said—he’s not working for us. And what they were discovering is that he’s a human being like them, with fallibilities and limitations, and they were wondering whether to carry on with the story. I said—this is where you need to look deeper into the story because you’ve actually cracked that first shell. You’ve gone beyond that, seeing it from the outside and the inside, you’ve seen something more. And you have to be able to tell the story now from that perspective. He’s a misfit. And in a community of poor people struggling to survive, how does a misfit live?

But how did they approach him initially? What has been the process of gathering these stories and developing them?

I came in a few days before the participants arrived and because I had been in Kochi before, I already knew some people here. The Kochi Biennale guys had a couple of younger volunteers whom they deputed to help me with this project. They’re from here, so once they understood the kind of thing I was looking for, they also did a little bit of recce and identifying. I came in a few days ahead and we started meeting these people. So that way, I built up a story bank of about 20 potential stories. And my lens was through the lens of the individual. So I’m not looking at the history of Kochi or the representatives of the different communities. All of that comes in, but through the lens of an individual person who practises a trade or skill; how these people are all, in their own ways, elements of how this city functions and survives.

Then the students came in. I went with all of them to each of these people and we had another round of talking, after which they started to identify the ones that they wanted to work on. Only two people decided to work in collaboration and the others took up their own stories individually.

And what are some of the other kinds of protagonists and stories that have emerged?

I was concerned about two things: firstly, that our stories shouldn’t be focused around only the majority community; and two, that there should be enough stories about women. Finally, out of those 20 we have 10 stories being worked upon. And interestingly, in the end, five of the stories are about Muslim characters. But about women, it didn’t work very well. Because it takes a lot longer to get to the stories of women. Women are always in the background. The men always come forward and their stories are upfront. They are engaging in public life, they are practising professions. Women are often at home, they’re bringing up children, they’re not really used to telling their own stories.

Are they possibly more reluctant to tell their stories as well?

Yes, it’s a psychological thing. In society, women are just not allowed to think that they have stories, that their stories are important. So I think it requires a much longer and deeper engagement to actually draw stories from women. There’s one which is about a female protagonist… but then, she’s not a typical family woman. She is the caretaker of a Sufi dargah and that dargah has a reputation that if men try to manage it, they meet a bad end. So it’s a woman-centric space. Her story comes up only because she is outside that whole system of family and patriarchy. In a couple of other stories, there are women characters who are peripheral. But that’s about it.

Recording the environment around us, the spaces we inhabit—these are central to the workshop and have also been at the core of your own work. Why is that so?

The artists whose work I was most deeply influenced by or whom I admired the most… even if it was a Surrealist like Dalí, for example, his very deep insight into human nature comes through even when he’s creating work that’s surreal or unreal, so to speak. Not only the insight into human nature, but also his sheer ability to observe—how exactly you hold that pen when you write. That observation, I believe, is at the root of all my artistic work. It’s not something only I do, I think it’s the human tendency to do that. I believe that our minds are like digital cameras that are taking photographs all the time of everything that you see and storing it somewhere in some huge hard drive. And I think that process of drawing is like a connection with your memory, your subconscious. The term ‘drawing’ itself to me has a second meaning, because it’s like drawing water from a well. Memory is like a well and as long as you draw, you can get it out. So that’s been a very basic part of my practice.

Your 1994 work The River of Stories on the Narmada Bachao Andolan is a great example of our relationship with the world around us. It’s also known as one of India’s earliest graphic novels. What’s your take on the term ‘graphic novel’ and how would you differentiate it from ‘comics’?

I’m okay with using the term ‘graphic novel’ to describe a genre of comics. But I certainly don’t agree that the graphic novel is a medium different from comics. The medium is one and the same. And there’s such great work that has been done in the medium over the years, that if you say this is not a comic, you’re actually denying the history of the whole medium. So when people say ‘you are India’s first graphic novelist,’ I’m okay because you’re telling me that I’m one of the first to experiment with the genre.

Much of your work carries a sense of political urgency and dissent. Why are comics relevant as a means of social observation and change in India, particularly in our present times?

People ask me sometimes—what’s ‘Indian’ about your graphic novel or all these so-called ‘Indian graphic novels’ that are coming out? To my mind, it’s not a superficial stylistic that defines what is Indian or Western. It’s actually the subject that the medium chooses to deal with that defines that. And I think in India, many people apart from me have somehow focused on social reality. Because Indian social reality is so complex and so diverse, you can’t help but address that. As an artist, you’d be pretty foolish to close your eyes to all of this. And in today’s times, it’s become even more urgent to talk about it. And because this medium speaks to young people, I think it’s even more a kind of responsibility for us to use it and create political awareness. I think Indian middle-class kids live in a kind of bubble. And my work right from the Narmada days has always been to pop that bubble.

At the same time, just because we should look at a social and political commitment as very ingrained in our work, it doesn’t mean that we compromise on the art, or the power of our stories, or the aesthetics of our constructions. It’s all part of the same thing. You have to be committed to your medium.

***

This interview was first published in the Indian Quarterly, a literary and cultural magazine.

Feature Image by Orijit Sen’s mother, from Orijit Sen’s personal collection.